Chaat Pack for street nibbles

December 16, 2005

Here is a chaat array being sold on the streets of Delhi. Check out the packaging stuffed in between the sacks of chaat.

You buy some chaat, the vendor mixes it up with some piquante sauce, and you’re good to go.

This is an example of how a food manufacturer together with a forward-thinking food designer used street food to inspire a new product for its street food-appreciative market in India. The chips are flavoured and (loosely) styled to reference ‘chaat’, a term describing all manner of street food snacks. If you look closely on the packaging, you’ll see an image of the traditional street chaat packaging on the left side. Within 10 metres of the stand where I photographed this package, there were five different traditional chaat vendors selling proper chaat.

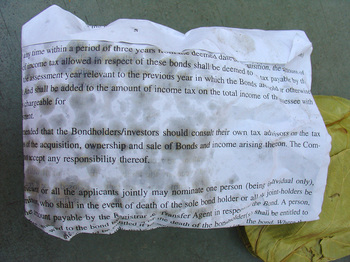

Packaging for chaat is usually a bag made from old newspaper, a neatly cut piece of recycled paper, or a leaf plate. This bag was made from some terribly interesting literature about bonds, you can see the imprint of the peas (and the grease in which they were deep-fried) absorbed through the paper. Grease shadows, or oily pea portraits, if you will.

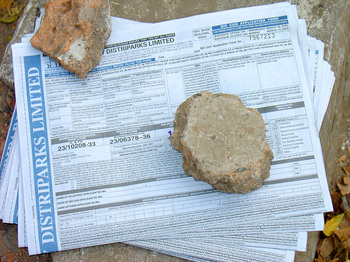

In this image you see a stack of paper left on the street as an offering to the gods of the recycled chaat-bag-makers.

debra at 9:16 | Comments (4) | post to del.icio.us

Chaat Street, Indian chips mimic street food golgappa

December 13, 2005

Nine months ago I was in Delhi and not in the Polar Circle at midwinter, and it was there that I was introduced to golgappa, one of the top ten amazing things you could ever hope to put into your mouth. The more I re-peruse the images of food from ElBulliFatDuckAlineaMoto and the likes, the more I can’t get this unpretentious street food out of my mind.

Golgappa is a deep-fried pastry pillow, neither sweet nor savoury, which is served up in a most intimate way. The street vendor pokes a hole in the deep-fried puff, gives you a metal or leafenware bowl and then asks you if you are ‘ready’.

Ready? you say, *lifting one eyebrow.

And he takes that as a ‘yes’.

The vendor proceeds to ladle a liquid into the golgappa that quite strongly resembles brackish pond water. In actuality it is a tasty, thirst-quenching tamarind drink with crispy puffs and bits of melon or turnip floating around in it. Neither sweet nor savoury, this soupy mixture is best described as ‘refreshing’.

The vendor then hands you an about-to-drip-and-disintegrate golgappa filled with the liquid and you have to pop the entire thing into your mouth where it implodes instantly, crunch and rinse, and you can do nothing but laugh and sop up the dribble on the shoulder of your friend’s blouse.

By this time the vendor has already started to dish up another one, (pop, crush, rinse and swallow) and another one, and another one. The idea is that you are popping golgappa into your mouth as fast as you can until you beg him to stop by motioning with your tamarindily dripping fingers. A recent study on street food has proved that ninety-four percent of first-time eaters of golgappa say ‘wowwy’ in response to the experience.

How wise it is then that Frito-Lay should be inspired by golgappa for their Street Chaat line of chips in India. Poke-free. Drip-free.

* - Poetic license. I can’t lift only one eyebrow.

debra at 18:04 | Comments (8) | post to del.icio.us

Occupied Olive Tree Territories

December 10, 2005

(A Palestinian farmer weeps at the bulldozing of his olive trees, photo by Gary Fields)

Because culiblog is a culinary weblog about food, food cultures, food as culture and so on, I feel obliged to breach the subject of olives, olive trees, olive tree culture, and olive trees as culture. In the past month I have seen Osama Qashoo’s documentary, My Dear Olive Tree, (at the IDFA), and Khalil Rabah’s installation piece (at the 9th International Istanbul Biennale), the Palestinian Museum of Natural History and Humankind. The olive tree as a symbol of Palestinian identity is used in both Rabah’s and Qashoo’s work.

Osama Qashoo is a recently exiled Palestinian film maker living and working in the UK. My Dear Olive Tree is his documentation of the destruction of the olive tree that he tended since childhood. The film depicts Qashoo as he witnesses the demolition of his olive tree and surrounding olive orchard, his own unwilling journey from Palestine to London, where he is reunited with a residual form of his dear olive tree on sale in an airport gift shop. At the beginning of the film Qashoo warns us that this is the last time he will see the olive tree, one tree of an entire grove in the Occupied Territories, a grove that sustained more than twenty families for generations with income from the olive oil.

still from My Dear Olive Tree, courtesy of Osama Qashoo

The eighteen-minute documentary shifts swiftly from registering the small community’s warm familial bond with the land, to an extremely tense situation in which Israeli Army bulldozers move in to uproot the olive trees. The film shows Palestinian women in a state of utter hysteria as they are forced to bear witness to an act nothing short of an amputation. The film ends with a visit to an airport gift shop presumably en route to the UK, where, in some twisted form of fundraising, olive wood pendants cut into peace doves are being sold. Filmmaker Qashoo buys one of the trinkets and in the mean time the audience seems to have scratched deep grooves into the arm rests of their seats.

Khalil Rabah is an internationally acclaimed artist working in the field of conceptual art, installation and performance. Together with Zvi Goldstein he was the recipient of the Lennon-Oko Grant for Peace in 2003. His work reminds me quite strongly of the Neue Slovenische Kunst style of re-claiming and re-writing one’s own history with regard to cultural identity. Rabah’s Palestine before Palestine museum exhibit uses the olive tree and the installation-form to parody the history-writing effect that such a museum institution wields by its very presence. Rabah embeds the present-day context of Palestine and Palestinian identity within the context of a natural history museum, by describing the entire natural world in terms of the (occupied) olive tree.

(images of the Palestinian Museum of Natural History and Humankind exhibit; Palestine before Palestine, courtesy of Khalil Rabah and the Istanbul Biennial)

In typical museum-style, the Palestinian Museum of Natural History and Humankind (PMNHH) opens cans of experts, declares facts and exhibits it’s acquisitions policy, manifest in projects such as the 3rd Annual Wall Zone Sale, an auction which took place at the Khalil Sakakini Cultural Centre in Ramallah in March of 2004. By auctioning off lots of material from around the wall zone, artist Rabah lobbied awareness of the social and ecological implications of the ~670km West Bank Barrier that Israel is currently building. The PMNHH also has a café and a giftshop, complete with very helpful attendents ready and waiting to attend. But when one asks in all earnestness for a cup of tea, or if there is something to buy in the giftshop, the attendant just shakes her head and smiles. ‘Sorry, we have nothing to sell.’

(Please read more… )

debra at 19:03 | Comments (11) | post to del.icio.us