Permaculture *relaxtivist

January 12, 2009

A thicket of rocket growing in the irrigation canals and dried mulch rotting on the beds.

Relaxed permaculture is what I’ve decided to call this gardening technique, tailor-tuned to my garden and me. One of the principles of permaculture is to keep the ground covered at all times with either plant matter or a thick layer of mulch. This technique simultaneously keeps out the ‘bad weeds’ while nourishing the soil with plant combinations and/or green manures. I hope the images that I’ve just taken of my kitchen garden at midwinter offer a clear illustration of some of the techniques that have been successful for me this year.

Brussels sprouts and broccoli in a sea of rocket.

My garden is left to its own devices for weeks, sometimes months on end each time I return to the far-away Polder Circle. I’ve developed a permaculture technique for growing green manure ground covers in situ, using them alive or folding them over (felting) into mats and letting them dry sur place. I place these mats on the beds, and plant my crop seedlings in between. The thick mat prevents weed growth, and within two seasons it rots in place, so that I’m always planting the vegetable seedlings in the ground that is most nourished with organic material. I don’t turn the soil, just aerate and loosen it up a bit with a pitchfork when I plant the new seedlings. This keeps the carbon underground and prevents the oxidation of soil nutrients.

Here’s how nature does it: a heap of horseradish rotting away, new shoots poking through the old leaves.

Plants left to their own devices do this naturally. See above how the horseradish holds its ground against plant competitors, covering the soil so that the new growth peeking through can monopolize the full plant foodtprint of sunlight and soil nutrients. I’ve sprinkled some wood ash to aid in the rottage.

Leggy bergamot being harvested for felted mulch in the upper garden, rocket on the right.

The above image shows the harvest process of my overgrown bergamot mint, (end of November) which I grow in the irrigation canals. At seaon’s end, I lay down the bergamot in swathes and chop it off at the base with my sharp and trusty Opinel. With a sweep of an overly muscular left arm, I roll the stalks into mats which I place on the paths or on the beds. The finished mat looks like lace, especially when you cut back long-stemmed plants like mints or alfalfa. And the chopped-off bergamot grows back instantaneously if not even more vigorously. The entire process smells like brewing a garden-sized pot of Earl Grey.

Lower garden broccoli babies growing in the summer’s phacelie hay, rocket in the canals.

When I want to plant a new crop, I just pull a hole in the mulch matting and plant the seedling. Outside the summer months, I’ve visited the garden every 6-8 weeks this year, and this technique has served me well. My garden is constantly producing edibles, shocking considering the months of neglect. In fact, it’s probably because I’m not around that I can grow even more green manures on my paths and canals, because I’m not treading on them all the time. In light of the hours spent in the garden, the difference in productivity between my gardens and those of my neighbours is extreme. This year the tall-growing mustard and phacelie also provided frost cover for the lower-lying brassicas and rocket. It’s January and my garden is full of leafy green produce.

By comparison, garden neighbour Monsieur C. wages his war on weeds by sealing off the soil from the great outdoors with large swathes of plastic.

To compare my relaxed permaculture with another technique, check out my petro-fertilising garden neighbour Monsieur C. Formally speaking, his technique is similar to mine except that he hermetically closes off the entire surface of his garden, denying access to light and rain (and weed seeds blowing in). Like me, C. also plants his crop in little holes cut out of the mat. His technique would be exquisite as an art installation but it also successfully wards off the potential for any scrap of organic matter from entering his pristine soil. (And you don’t call it soil for nuthin’.) Essentially he’s growing hydroponically with nutrients sourced from chemical fertilizers. When C. returns to his garden in April he will spend no time weeding. Instead he will spend time removing the stones, laying out and rolling up the large black plastic mats, and driving his car to and from the garden centre for a steady fix of petro-chemicals. His garden is highly productive and brings him and his family lots of joy.

Because my gardens are upstream and more often than not upwind, in his case I can be generous (and by generous I mean self-righteous and cranky) and declare, ‘to each his own’.

- *Permaculture Activist is the name of an informative quarterly about permaculture in the broadest sense of the word. Don’t mind the bears. And the beards.

debra at 14:56 | Comments (0) | post to del.icio.us

Michel Blazy’s microbial art

December 18, 2008

A pond of fermenting tea with fungal lily pads

The lacto-fermentation of cabbage wasn’t the only kind of microbial art and design going down in St. Etienne at last month’s biennial. Michel Blazy created a most beautiful live installation of Givernyesque pools of living kombucha colonies. For those not yet in the know, kombucha is a fermented tea, that folks east of Caucasus can’t get enough of. It’s made with a fungus that imparts such special health-giving properties that kombucha enthusiasts call it the ‘elixir of life’. Kombucha is a slightly soured, bubbly, probiotic drink.

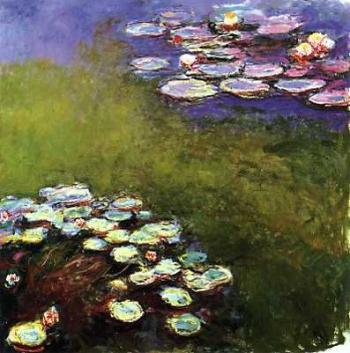

Blazy’s reflective pools conjure microbial Monet

As a point of reference, Claude Monet’s ‘Nympheas’ at the Museum Marmottan in Paris, image obviously used without permission

Michel Blazy is a French artist whose sculptures and installations are process-based interactions between food materials and the direct environment. In the Palais de Tokyo in 2007 Blazy produced an aesthetically charged installation using sprouted lentils, yoghurt wallpaper and enormous pasta sculptures. Blazy’s work is sensually humorous but demonstrates a masterful materials synergy - productively harnessing the natural properties of foods and organisms. Think Roman Signer and Olafur Eliasson, but then with foods.

Growing kombucha fungi on a pond of green tea

For the ‘off-biennial’ venue of the Entrep˘ts Bellevue in St. Etienne, Blazy and his team made giant pools of tea which they fermented with a rainbow array of gelatinous lily pads, rubbery, macroscopic fungal colonies that lent the ponds their healthful properties and a bit of bubble. Thinking the 1% alcoholic content might not be sufficiently festive for a vernissage, Blazy spiked his kombucha tea with celebratory shots of vodka and the atmosphere at the Entrep˘ts Bellevue was magic.

Pondering the depths, ‘Is it a pond or a pad?’

Blazy’s multicoloured spent tea bags

A greenhouse incubating kombucha offspring

Master of mothers, Blazy tends to his colonies

- Michel Blazy, JUS DE NYMPHEAS, Entrep˘ts Bellevue, St. Etienne 11 bis rue de lĺ╔galerie ľ 42 100 Saint ╔tienne, opening 20.nov.2008 until ???

Claude Monet’s later paintings include the Nymphea or Lily pad paintings

It’s been claimed that Kombucha: increases longevity, cures cancer, cures rheumatism, improves vision, prolongs sexual appetite and performance, cures bronchitis and asthma, cures kidney illnesses, cures cataracts, cures cardiac illnesses, cures diabetes, cures diarrhea, takes away white hair, grows black hair, is effective against herpes, increases appetite and helps digestion, cures insomnia, lowers hypertension, reverses the symptoms of AIDS.

How to make Kombucha - you know you want to.

DAMn░ Magazine writer Anneke Bokern on probiotic art

Superb (and hilarious) YouTube interview with Michel Blazy about his work - en Franšais.

debra at 12:44 | Comments (0) | post to del.icio.us

Permaculture in the Winter Kitchen Garden

December 11, 2008

‘Felting’ the leggy bergamot mint now lining the canals into a fragrant mat of living mulch

A missed flight back up to the Polar Circle from St. Etienne presented me the opportunity of a few days down south. I took the time to enjoy some rejuvenating familialarity and to tidy up the garden for winter. It never ceases to amaze me how efficient permaculture gardening is in the face of repeated absence and outright neglect. In just two afternoons I had more or less prepared the garden for the frosty days of winter, tucking the abundant edibles under living green manure plants and blanketing their beds with the now-rotted mulch harvested from the paths.

Image colours and lighting UNretouched

In the lower garden my task consisted only of harvesting the rocket-filled the canals and cutting a cabbage or two for choucroute from the beds. The mustard green manures had grown tall and seem to be protecting the low-lying rocket, coriander and curly-leaf parsley from the nightly frost.

Copious mizuna lettuce, sorrel and borage amongst phaecelie green manure

In the coldest corner of my upper garden, sorrel, mizuna lettuce and borage (and an invisible cassis) are burgeoning amongst the phaecelie green manure. The adjacent bed (not pictured) grows the most exquisite lacy purple salad mustard, protected from the cold by horseradish and rhubarb. Can you believe that I actually harvested rhubarb in the chilliness of November!

Permaculture perfect for in absentia gardening

Although I left the garden on its lonesome since mid-August, a timely planting of crop and green manures, strategic mulching and permaculture frost protection meant that the garden was full of food at the icy end of November. If the hardy green manures continue to protect against the frost, we’ll be eating fresh leafy greens, crucifers and brassica at midwinter and into the Hungry Gap.

-

More information on growing your own mulch in-situ here. I’ve been experimenting with building soil productivity, tilth and keeping weeds at bay by growing specific varieties of alfalfa, phaecelie, and mustard on the paths, and mints and clovers in the canals. Before leaving for a few months, I seed the paths with the GMOs (green manure organisms ; ) and upon my return I either pull or cut back the growth, and lay it back down on the paths where it gets trampled into a 10cm mat.

Whenever I need a big blanket of mulch for the beds, I just pick up the matted mulch from the paths which has more or less felted itself into a large bed-sized swathe, and lay it upside down on the beds. This mulch blanket keeps the beds free of weeds, helps prevent evaporation in the summer months and in the course of the season rots into something nutritious for the plants that I grow in between. This is turning out to be a very effective and productive method for my in absentia style of permaculture gardening.

Alfalfa can grow anywhere and is extremely hardy. But beware: one single plant grows to one cubic meter above ground with 10cm thick roots going down 1 meter. Once you plant this, you will not be able to get rid of it, so plant it judiciously. Alfalfa will ‘weed’ itself if you just let it get big enough so that you only have a few plants growing in your garden. Just keep it cut back to the bone and you’ll have lots of fibrous mulch material. As a plant, alfalfa is excellent for creating a moist micro climate. The growth, cut and ‘felted’ is excellent for rotting into mats to improve soil tilth. Yet I would not recommend planting alfalfa unless you have crap, untillable soil because it is very difficult to eradicate if you should want to plant something else in its place. It would be perfect for converting large areas with poor soil tilth (soils so compacted that you can’t cut into them with a pitch fork) into something usable within the course of a year. Alfalfa produces beautiful purple and blue flowers that the bees love and working in and around it smells magnificent.

Mustard is easy to grow, is edible and is easy to pull, a quality that I value in a green manure. As a ground cover it is not as dense as alfalfa or clover, but because it grows tall and leggy, it will protect plants growing in between it from frost and provide dappled shade and keeping the micro-climate 40 cm under the plant canopied and wet. It does not produce huge amounts of biomass for mulch, but it flowers nicely and I will continue to work with it.

Phaecelie is easy to grow, produces pretty purple flowers in the spring and is very easy to pull. As a green manure it has many of the same qualities of mustard but it locks in (soil) moisture better (is a ‘fatter’ plant). As far as I know, it is not edible but I will continue to work with it.

Ground clover: This was already growing in my upper garden canals and I tried to eradicate it a few years ago. Fortunately I was unsuccessful. This is a great green manure for the beds where it fixes nitrogen in the soil and grows very densely, keeping all other weeds at bay. When you want to plant a bed, pull the clover (which will return, don’t sweat it) and make space for your desired planting. This is an excellent roaming ground cover for areas where ‘roaming’ is appropriate - in places where you want to eradicate grasses, for example. It flowers and smells nice when you walk on it, making it perfect for lining irrigation canals.

Soybeans: For the life of me I can not get these to grow in any useful way. Although soybeans are supposed to be great for nitrogenating the soil and I of course DREAM of edamame parties in the garden, my plants never grow higher than 15 cm high. It is possible that soybeans don’t do very well with my absence, and need more encouragement in their early days. This year I will try a more emotionally hardy variety.

Mints and bergamot: Officially these are not green manures, but I’ve been growing these plants in my irrigation canals where they are prodigious, attract bees and smell fantastic when you so much as brush past. In the winter you can cut them back and they will grow anew in the spring. This year I’m experimenting if the leggy growth that I cut off these plants will re-root in my lower garden, where I am waging a 4 year battle against an aggressive Jerusalem Artichoke. My hope is that the bergamot/mint will take root and densely discourage the topinambours from taking over. Mints are easy to remove should you want to plant something else, they smell wonderful, and shade the canals and beds, preserving the moisture. Bergamot in particular is extremely fragrant and when you’re around, you can keep the plants you’ve planted in canals or on the paths under control by just treading on them. Perfumed steps!

debra at 13:26 | Comments (0) | post to del.icio.us